On Thin Ice

Asia is a land of extremes. It is home to the world’s highest mountains, the largest swamps and flood plains, and the largest reservoir. It is also home to permafrost that extends to lower latitudes than anywhere else in the world. But as global temperatures rise, that permafrost is thawing and posing challenges for the region’s infrastructure.

While the greatest threat is environmental, the impact on infrastructure is also alarming. By definition, permafrost is frozen ground that remains below 0°C for at least two years. When it melts, it can shift ground, change drainage patterns, and loosen debris. These movements dramatically raise infrastructure maintenance costs, and in some areas, increase the risk of landslides. By one estimate, global costs associated with permafrost thawing could approach $150 billion a year by 2030.

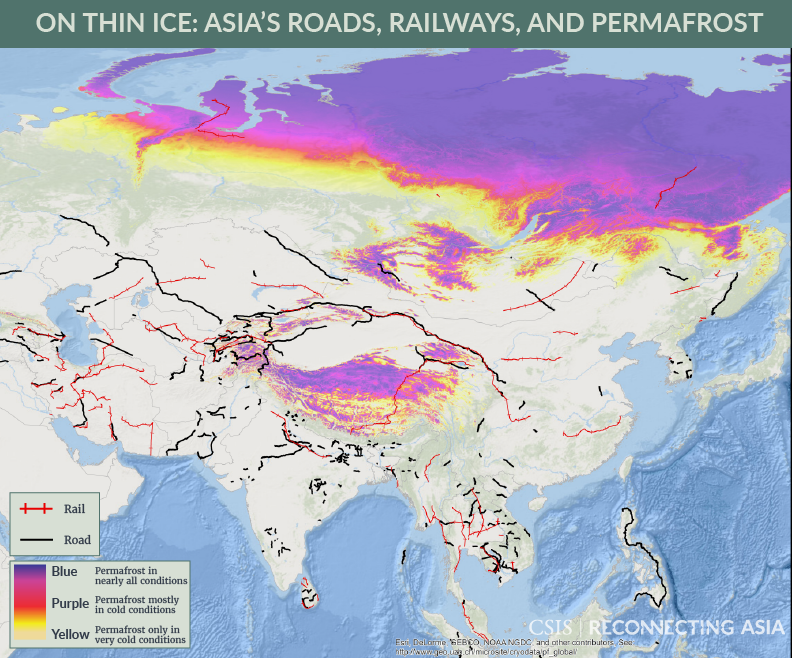

To begin exploring these challenges, we’ve combined permafrost data from the University of Zurich with Reconnecting Asia’s data on roads and railways. In the map below, blue indicates permafrost that exists nearly everywhere. Yellow indicates permafrost that only exists in the most favorable conditions. Actual conditions on the ground can vary widely, depending on sun exposure, vegetation, and snow cover, among other local factors. But the permafrost data is helpful as a general guide, particularly in areas where data collection is limited.

As the map illustrates, Asia’s permafrost is concentrated in a number of areas: Russia, China, Mongolia, parts of Central Asia, and surrounding mountain ranges. The infrastructure data is not exhaustive of existing or planned projects, but helps to highlight some affected areas. The vast majority of Asia’s permafrost does not touch developed or developing areas. But where it does, rising temperatures can pose a significant risk.

Consider Russia. A new study estimates that at least 25 percent of Russia’s permafrost-exposed infrastructure could be destabilized by mid-century. In Yakutsk, the largest city in the world built on permafrost, a 1.5°C increase in mean annual air temperature could deform almost all building foundations. While Russia’s northern ports could benefit from rising temperatures, its ground transportation networks will need to adapt. That includes large sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which carries more than half of the foreign cargo that passes through Russia.

Despite advances in engineering, permafrost still poses challenges for recent and planned projects. China’s railway to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, crosses nearly 700 miles of permafrost. Opened in 2006, the line uses overpasses, crushed layers of rock for insulation, and even pipes that circulate liquid nitrogen. But construction can also accelerate the thawing, and as temperatures continue rising, experts disagree about how long these adaptations will allow the line to function.

Looking ahead, enhanced monitoring and sharing best practices could help reduce risks. In many areas, data collection is still sparse. With improved monitoring, existing infrastructure can be watched closely as local conditions change. There is also space for public and private collaboration. Engineers and scientists from China, Europe, Russia, and the United States have valuable knowledge to share. Future projects must factor climate change into life-cycle cost estimates. For developing and developed countries alike, climate resilience is not a luxury but a necessity.

Of course, thawing permafrost is just one symptom of a much greater challenge. Climate change impacts infrastructure in a number of ways. Heat waves expand bridge joints and crack paved surfaces. Rising sea levels and storm surges increase the risk of flooding and coastal erosion. Heavy rain makes landslides more likely. The challenge extends well beyond infrastructure, and ultimately, so must the solutions. Only global cooperation can make local infrastructure truly sustainable.

Jonathan Hillman is the Director of the Reconnecting Asia Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.