Too Good to be True

Why Kazakhstan’s “New Dubai” May Deserve a “Don’t Buy” Rating

Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev is a man of vision. In the 1990s, he envisioned a new capital, Astana, rising out of mostly empty Central Asian steppe. It is there today, complete with a Western-style university and Norman Foster buildings. In 2014, he envisioned a “New Dubai,” Khorgos, on Kazakhstan’s southeastern border with China, part of the Nurly Zhol plan that marks its two-year anniversary this month. When I made the five-plus hour car trip from Almaty to Khorgos earlier this year, three massive container gantry cranes, dormitories for thousands of workers, and a burgeoning logistics zone at the site were among the many signs of this vision emerging. By 2050, Nazarbayev sees Kazakhstan as one of the world’s most competitive economies, with big infrastructure investments like Khorgos central to achieving that goal. It is not impossible that this vision, too, will emerge in its time; but as it turns two, it is already looking likely that Khorgos will struggle to match Astana’s ambitions—a reminder of some of the larger challenges that Nazarbayev and Kazakhstan will have to overcome on the road to 2050.

Located at the border between Kazakhstan’s Almaty province and China’s turbulent Xinjiang autonomous region, Khorgos Gateway is a signature effort for leaders in both Astana and Beijing. The combined dry port, logistics zone, and industrial zone is a central component of Nazarbayev’s Nurly Zhol, and represents a major investment in diversifying Kazakhstan’s hydrocarbon-dependent economy. It is also a key node in the “Silk Road Economic Belt,” the overland component of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) initiative, the aims of which include developing China’s troubled western regions and creating new trade opportunities—as well as supporting a geostrategic push to enhance China’s political, economic, and cultural influence across Eurasia.

For both countries, Khorgos represents an important test of OBOR’s viability. Accordingly, Astana has high expectations for the combined dry port, logistics center, and free trade zone (FTZ) that some commentators have dubbed Kazakhstan’s “New Dubai.” By 2020, the Kazakh government has projected that the dry port and associated free trade zone will support 50,000 jobs and see annual throughput of 500,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs). For context, that would employ around 40 percent of the total population of Almaty’s Panfilov District, where Khorgos is located, and represent a greater-than twentyfold expansion in traffic volume over current levels.

Judged against the scale of Beijing’s ambitions for OBOR, these goals might seem, if anything, a bit too modest. After all, even were Khorgos to exceed its 2020 traffic target, it would still not crack the list of China’s top twenty ports by volume. However, the viability of the project as a commercial proposition and its ability to achieve the aforementioned targets are far from assured.

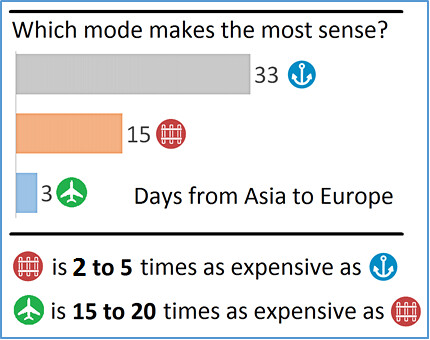

To succeed, Khorgos will need to attract increased traffic volume, and tap into the $600 billion China-Europe trade relationship (though it might also provide a gateway to the Eurasian Economic Union). Rail represents an attractive middle option between air and maritime freight shipping, less costly and carbon-intensive than the former and far faster than the latter. Prior to the completion of Khorgos and the 293 kilometer Zhetygen-Altynkol rail line in 2012, the only rail juncture between Kazakhstan and China was the Soviet-era connection at nearby Dostyk. Khorgos enjoys a number of advantages relative to its neighbor: a paperless clearing process, more efficient transloading capabilities (required to navigate Sino-Soviet rail gauge differences), better storage facilities, and even calmer weather.

Other improvements are also happening throughout the China-Europe logistics network designed to improve the reach, flexibility, efficiency, and overall attractiveness of the trans-Eurasian land transportation network. These include new investments at the Alyat port complex in Azerbaijan and at Anaklia in Georgia, as well as proliferating transnational agreements. Given all of this activity, and the fact that container traffic between China and Kazakhstan by rail reportedly increased 18-fold from 2011 to 2014, there is a logic to the rapid growth that Astana is targeting.

But there are limits to how much traffic Khorgos can realistically attract. Recent sky-high growth rates mainly reflect that China-Kazakh rail traffic was starting from an extremely low base, slightly over 1,000 TEUs in 2011. Even as container traffic rose in 2015, tonnage through Khorgos fell almost 50 percent. Given that GDP growth is slow or slowing on both ends of the China-Europe route, and global trade growth for 2016 is expected to be the lowest since the global financial crisis, Astana’s targets may prove to be overly optimistic.

Trans-Eurasian rail freight will also have to overcome a range of hurdles. The cost per TEU of rail shipping between China and Europe remains 2-5 times as expensive as sea freight. Air freight may be more vulnerable, but already handles comparatively limited volume and its speed will continue to offer a built-in advantage for certain goods. Rail’s current level of competitiveness also depends on extensive subsidies throughout the supply chain, from direct transport subsidies by local Chinese governments to various production and input subsidies offered by inland Chinese cities. And these market-distorting incentives work mainly in one direction: the volume of traffic from Europe to China is around 60 percent of eastbound traffic, often requiring trains to make the return trip empty (and raising costs for shippers).

Predictability is another a problem. Trans-Eurasian rail routes must either use deteriorating Russian routes to Europe or cross numerous national boundaries. Many of the latter are controlled by countries that suffer from high levels of corruption and struggle to trade efficiently across borders. Often the relationships between neighbors on either side are historically fraught. Unexpected delays anywhere along a route—whether politically motivated, the consequence of poor soft infrastructure, or resulting from maintenance failures across thousands of kilometers of track—can easily raise costs and deter customers.

Khorgos’s industrial zone also faces challenges. The devaluation of Kazakhstan’s currency in 2014 and 2015 should have boosted the manufacturing competitiveness of Kazakhstan’s commodity-dependent economy. Yet, shops on the Chinese side of the Khorgos border are routinely filled with Kazakh customers who have traveled from across Almaty province to buy cheap Chinese goods for their homes and for resale in local markets. This is no surprise: the population of Xinjiang alone is almost 40 percent greater than that of Kazakhstan. Promises of millions of dollars of Chinese investment aside, strengthening transport linkages to the “world’s factory” might not help Astana’s diversification agenda.

None of this is to say that Khorgos is bound to fail, either as a logistics hub or an industrial zone. Though the trees promised in its promotional materials seem a bit far-fetched, arriving by car and seeing the massive yellow container cranes rising out of the steppe offers a powerful reminder of the seriousness with which Astana and Beijing are attempting to overcome the boundaries of geography. And just as unpredictable global trends, such as slow growth, climate change, and automated manufacturing, magnify the uncertainty surrounding its future (and that of Kazakhstan itself), there are factors that could break in its favor. Even if Khorgos is not a commercially viable investment, its existence has already changed the tracks on the ground. It will compete for business with other transport routes, facilitate new people-to-people ties, and represent a high-profile test of OBOR’s larger viability. What remains to be seen is whether it was money well spent, and exactly who will reap the benefits.

David A. Parker is an associate fellow with the William E. Simon Chair in Political Economy at CSIS